“Today, the entire Western financial world holds its breath every time the Fed chairman speaks, so influential are the central bank’s decisions on markets, interest rates and the economy in general. Yet the Fed, supposedly created to smooth out business cycles and prevent disruptive economic downswings like the Great Depression, has actually done the opposite.”

— Federal Reserve Governor Ben Bernanke, Nov. 8, 2002

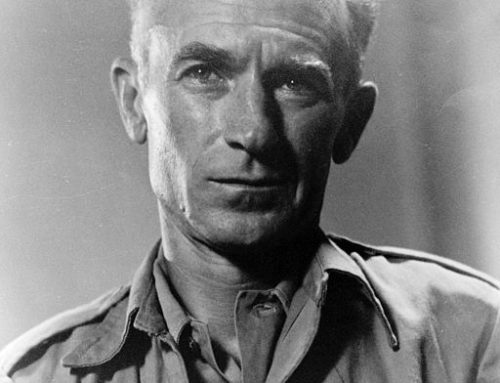

In 2006, President George W. Bush appointed Ben Bernanke as chairman of the Federal Reserve, the gatekeeper of the U.S. economy.

Among the Fed’s duties and goals:

Influence monetary policy in order to pursue maximum employment, keep prices stable and moderate long-term interest rates.

Supervise and regulate banking institutions to ensure the safety and soundness of the nation’s banking and financial system.

Maintain the stability of the financial system.

Contain systemic risk that may arise in financial markets.

Bernanke now must defend his policies in order to win reappointment in January to a second four-year term as Fed chairman.

In a July 25 New York Times op-ed piece, “The Great Preventer,” Nouriel Roubini wrote: “Mr. Bernanke deserves to be reappointed. Both the conventional and unconventional decisions made by this scholar of the Great Depression prevented the Great Recession of 2008-2009 from turning into the Great Depression 2.0.”

Bernanke spent trillions of taxpayer dollars to save the system. During his tenure, the Fed cut interest rates nearly to zero; launched innovative programs to support money market funds, facilitate mortgages, provide short-term lending to small business and provide student loans; doubled the size of the Fed’s balance sheet; and conceptualized the direct capital injection of $250 billion of TARP money directly into nine of nation’s largest banks.

At long last we are beginning to see “green shoots” of recovery. Leading economic indicators have turned positive, and some major banks are attracting private investment again. Most economists now forecast small positive growth for 2010 and 2011.

At a speech before the National Press Club on Feb. 18 in Washington, Bernanke defended his record.

“Extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures,” he said. “Responding to the very difficult economic and financial challenges we face, the Federal Reserve has gone beyond traditional monetary policy making to develop new policy tools to address the dysfunctions in the nation’s credit markets.”

Ironically, Anna Schwartz, who co-authored with Milton Friedman “The Monetary History of the United States,” the book that launched the free-market counterattack against Keynesianism in the early ’60s, has become an outspoken critic of Bernanke.

Schwartz made two strong arguments against Bernanke’s policies. First, she worried that the doubling or tripling of the Federal Reserve balance sheet under Bernanke will unleash a wave of inflation. She pointed out that Bernanke did not possess an exit strategy to remove the trillions of dollars of toxic assets from the Federal Reserve balance sheets. Secondly, she argued that Bernanke has neither provided transparency nor articulated a set of principles.

She pointed out Bernanke’s contrarian actions. On the one hand, the Fed collaborated with the Treasury to save Bear Stearns and AIG, and on the other hand they let Lehman Brothers fail.

What would Friedman say about Bernanke’s tenure?

Bernanke understands the Fed’s prescription failures during the Great Depression. Its tight monetary policy during contractions worsened the country’s economic free fall. Bernanke has certainly not repeated the mistake.

On the other hand, Bernanke’s Federal Reserve has possibly failed to perform its primary mission of “smoothing our business cycles.”

Bernanke’s Fed may have prevented another Depression. However, the Fed has poured too much liquidity into our monetary system in order to ward off the downturn. Easy monetary policies might prolong a boom in a few years that would lead to super-inflation.

Originally published in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune