Introduction

I was not made aware of the internment of about 112,000 persons of Japanese ancestry who lived on the U.S. mainland, mostly along the Pacific Coast, until about 20 years ago. About two-thirds of them were full citizens, born and raised in the United States. Virtually all Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes and property and live in camps for most of the WWII. The government cited national security as justification for this policy, although it violated many of the most essential constitutional rights of Japanese Americans.

In 1988 Congress passed and President Reagan signed Public Law 100-383 that acknowledged the injustice of the internment. The United Government apologized for it and provided $20,000 cash payment to each person who was incarcerated.

Main Story

Pearl Harbor, and the Japanese victories in Guam, Malaya, and the Philippines, fueled anti-Japanese American hysteria. Both the Office of Naval Intelligence and the Federal Bureau of Investigation felt that the Japanese American population did not pose a significant threat to national security.

Many Pacific Coast citizens and Newspapers argued that local Japanese Americans might help the Japanese military launch attacks in their region. Walter Lippmann, a very influential journalist, argued that the only reason why Japanese Americans had not been caught plotting an act of sabotage was that they were waiting to strike when it would be most effective. Another influential columnist, Westbrook Pegler, wrote, “The Japanese in California should be under armed guard to the last man and woman right now and to hell with habeas corpus until the danger is over.”

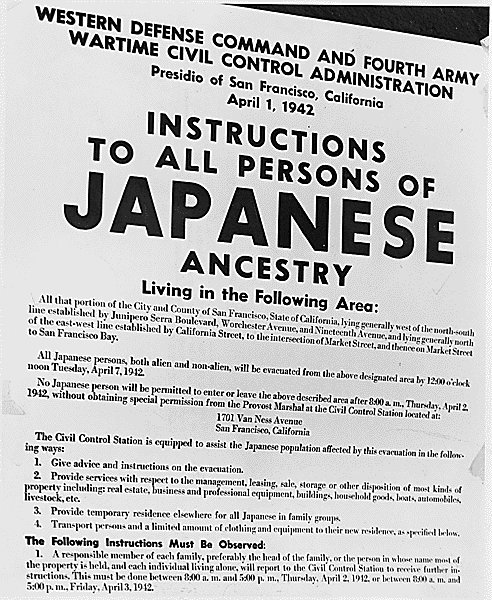

Neither Attorney General Francis Biddle nor Secretary of War Henry Stimson initially believed the removal would be wise or even legal. However, military leaders insisted that internment was necessary to ensure public safety on the Pacific Coast. Between the public demand for action and pressure from the military, Biddle buckled and told Stimson he would not object to a wholesale removal of Japanese Americans from the region. Stimson advised Roosevelt accordingly, and on February 19, 1942, the President signed Executive Order 9066, which directed the War Department to create “military areas” that anyone could be excluded from for essentially any reason.

The newly created War Relocation Authority did move Japanese evacuees into a series of “relocation centers” for most of the rest of the war. Families were given only a few days to dispose of their property and report to temporary “assembly centers,” where they were held until the larger relocation centers were ready to receive them. Living conditions in these makeshift camps were terrible. One assembly center established at Santa Anita Park, a racetrack in southern California, housed entire families in horse stalls with dirt floors.

The more permanent relocation centers were not much better. The War Relocation Authority established 10 of these camps, mostly located in the West. The Army-style barracks built to house the evacuees offered little protection from the intense heat and cold, and families were often forced to live together, offering little privacy. The residents were not required to work, but the guard towers and barbed-wire fences surrounding the camps denied them the freedom to move about as they pleased.

Despite these conditions, the incarcerated Japanese Americans did what they could to make the camps feel as much like home as possible. They established newspapers, markets, schools, and even police and fire departments.

In December 1944, the Roosevelt Administration declared the period of “military necessity” for relocation over, and officials began allowing Japanese Americans back into the Pacific Coast region.

The Japanese American relocation program had significant consequences. Camp residents lost some $400 million in property during their incarceration. Congress provided $38 million in reparations in 1948 and forty years later paid an additional $20,000 to each surviving individual who had been detained in the camps.

The Japanese American community itself was also transformed by this experience. Before the war, most Japanese Americans adhered closely to the customs and traditions enforced by their oldest generation (called Issei), which often deepened their isolation from mainstream American society. The experience of living in the camps largely ended this pattern for second-generation Japanese Americans (called Nisei), who after the war became some of the best-educated and most successful members of their communities.

Supreme Court Decision

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that upheld the internment of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II.

Fred Korematsu, a 23-year-old Japanese American argued that Executive Order 9068 was unconstitutional and violated the Fifth Amendment. He was arrested and convicted.

In a majority opinion joined by five other justices, Associate Justice Hugo Black held that the need to protect against espionage by Japan outweighed the rights of Americans of Japanese ancestry. Black wrote that “Korematsu was not excluded from the Military Area because of hostility to him or his race”, but rather “because the properly constituted military authorities…decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast” during the war against Japan.

Dissenting justices Frank Murphy, Robert H. Jackson, and Owen J. Roberts all criticized the exclusion as racially discriminatory; Murphy wrote that the exclusion of Japanese “falls into the ugly abyss of racism” and resembled “the abhorrent and despicable treatment of minority groups by the dictatorial tyrannies which this nation is now pledged to destroy.”

Korematsu’s conviction was voided by a California district court in 1983 on the grounds that Solicitor General Charles H. Fahy had suppressed a report from the Office of Naval Intelligence which stated there was no evidence that Japanese Americans were acting as spies for Japan.

The decision has been widely criticized,[1] with some scholars describing it as “an odious and discredited artifact of popular bigotry”,[2] and as “a stain on American jurisprudence”.[3] The case is often cited as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time.[4][5][6] Chief Justice John Roberts repudiated the Korematsu decision in his majority opinion in the 2018 case of Trump v. Hawaii.[7][8]