“I think the reality is that college athletics has become a profit maximizing endeavor for athletics administrators and coaches. And pretty much every else is left kind of holding the bag.”

-Jack Kroll, a board member of Colorado’s Board of Regents

Gambling will “have a corrosive and detrimental impact on student-athletes and the general student body alike.”

-Heather Lyke, the athletic director at the University of Pittsburgh

On November 20, the New York Times reported that eight universities are now working with online betting organizations to encourage gambling by students (some under 21). Some of the schools mentioned were Michigan State, the University of Colorado, and Louisiana State University. Many more schools are expected to introduce their students and sports fans to online gambling. In addition, at least a dozen athletic departments and booster clubs have signed agreements with brick-and-mortar casinos.

At L.S.U., Caesars promotions downplay the risk of losing. In an email, gamblers were told they could bet “on all the sports you love right from the palm of your hand, and every bet earns more with Caesars Rewards — win or lose.”

To secure these partnerships, athletic departments depend on the companies that handle the promotional and advertising rights for their teams. These companies, which arrange all kinds of deals with sponsors, act as middlemen. They negotiate the agreements with betting companies and take a cut, sometimes in the millions of dollars, on whatever money changes hands.

The question that the New York Times raised that I share is whether these partnerships that promote gambling on campus, fits the mission of higher education.

Certain factors make students especially vulnerable to gambling problems, including their age, stress levels and histories of substance abuse or depression.

“From mid-teens through 25, your brain is still developing,” said Ms. Drexler, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. One manifestation of that is poor impulse control.

Yet school-sponsored websites incentivize students to gamble by suggesting they have little or nothing to lose.

To understand how gambling moved onto campuses, The New York Times reviewed school records and interviewed students, professors, administrators, sports conference officials, gambling executives and counselors.

The deals came together largely in private, The Times found, with minimal discussion on campus about their potential impact on students, athletes and the integrity of college sports.

For example, the University of Colorado Bolder accepted $1.6 million to promote sports gambling. In addition, Caesars Sportsbook offered the school an extra $30 every time someone downloaded the company’s app and used a promotional code to place a bet.

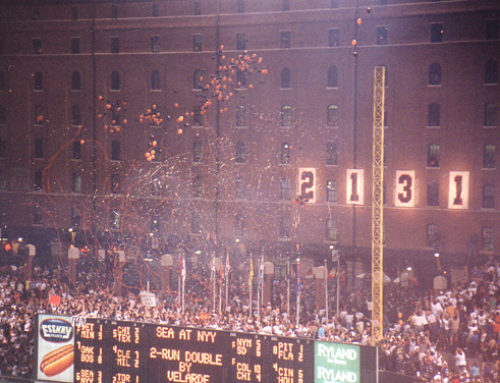

The gambling deals were part of a far-reaching but secretive campaign by the nascent online sports-gambling industry. Ever since the Supreme Court’s decision in 2018 to let states legalize such betting, gambling companies have been racing to convert traditional casino customers, fantasy sports aficionados and players of online games into a new generation of digital gamblers. Major universities, with their tens of thousands of alumni and a captive audience of easy-to-reach students, have emerged as an especially enticing target.

Mr. Haller, Michigan State’s athletic director, said in a news release at the time of the Caesars deal that it would provide “significant resources to support the growing needs of each of our varsity programs.”

Some aspects of the deals also appear to violate the gambling industry’s own rules against marketing to underage people. The “Responsible Marketing Code” published by the American Gaming Association, the umbrella group for the industry, says sports betting should not be advertised on college campuses. Unfortunately, gambling is now promoted on a widespread bases to college students and their alumni.

Most online gambling partnerships are just months old, so the full impact on students has yet to play out. But the risks are considerable. Sportsbooks encourage people to bet frequently, even after they rack up losses. Campus programs to treat gambling addiction and other problems are sparse, according to university officials and mental health experts.

Because gambling is not featured on school tours or in university brochures, parents may not know their children are enrolled in colleges where gambling is encouraged through free bets, loyalty programs and bonuses.

The New York Times reported that LSU sent a mass email to their students, some under the age of 21, the legal betting age in the state.

During the pandemic, many universities struggled financially. Michigan State’s athletics department, for example, ran a $15.4 million deficit in the 2020-21 school year, according to documents provided to USA Today. To help fill those holes, public and private universities nationwide have been scrambling to line up new revenue sources, including by arranging sponsorship deals.

For gambling companies, universities represent a big opportunity. In 2021, 47 percent of college graduates bet on sports compared with 22 percent of those with high school degrees, according to a survey by the National Council on Problem Gambling.

The Universities have proposed paltry funding–$25,000—to educate athletes about gambling. Universities are ill equipped to identify students who show early signs of gambling disorders.

The former president of L.S.U., F. King Alexander, said students were under enough pressure without the negative consequences of gambling. “The students are looking at X amount of debt and then the university is endorsing gambling on top of that?” asked Mr. King, who left before the Caesars deal was negotiated.