After 10 years, Jim Abbott retired in1999 with a career record of 87-108.

Imperfect relates the spectacular story of Jim Abbott who was born with one hand and yet went on to pitch 10 years in the Major Leagues, including a no hitter. Abbott shared with us his triumphs, failures, dreams and disappointments. For me learning how he coped with his failures and disappointments made me contemplate my own life.

When Jim Abbott was born, few would have predicted his successes. He was born to unwed lower middle class parents. At the time his mother had just started college and his father was in high school. Their Roman Catholic Church would not allow the couple to get married while the mother was pregnant. They married three weeks after Jim was born. Subsequently, through incredible persistence his mother graduated from law school and his father ultimately owned a brew distributorship.

As one would expect Jim encountered a variety of experiences-some wonderful, some hurtful. At each stage in his development as an athlete Jim faced negativity. It took repeated tries for his local schoolmates to let Jim play baseball with them. They questioned whether he could bat the ball. Ultimately, Jim not only was a standout pitcher but also batted over 400 in high school. Jim’s baseball coach convinced him he could also be quarterback on the football team, teaching him how to take a snap. As a high school quarterback, Jim led his team to the state finals.

As a amateur pitcher, Jim was a standout at the University of Michigan. He won an “unofficial” gold medal at the 1988 Summer Olympics.

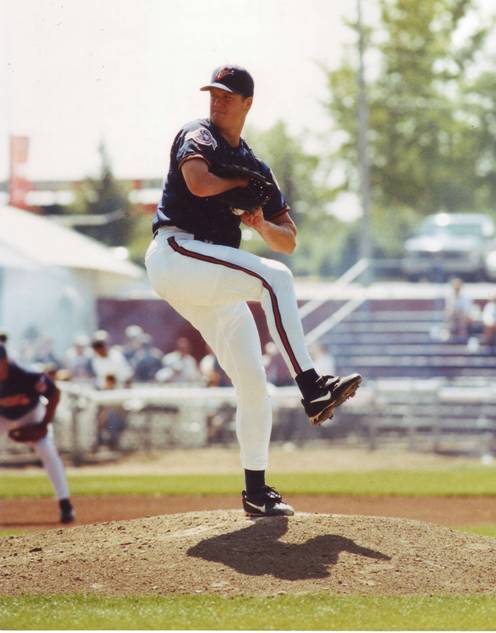

Playing with one hand

When preparing to pitch the ball, Abbott would rest his glove on the end of his right forearm. After releasing the ball, he would quickly slip his hand into the glove, usually in time to field any balls that a two-handed pitcher would be able to field. Then he would secure the glove between his right forearm and torso, slip his hand out of the glove, and remove the ball from the glove, usually in time to throw out the runner at first or sometimes even start a double play. At all levels, teams tried to exploit his fielding disadvantage by repeatedly bunting to him.

Batting was not an issue for Abbott for the majority of his career, since the American League uses the designated hitter, and he played only two seasons in the interleague play era. Abbott tripled in a spring training game in 1991 off Rick Reuschel, and when Abbott joined the National League’s Milwaukee Brewers in 1999, he had two hits in 21 at-bats, both off Jon Lieber.

One of the moving episodes in the book is when a teacher taught him how to tie his shoes with one hand. For several evenings the teacher practiced the task before accomplishing it. He then taught Jim to achieve this. Prior to that, Jim’s parents double and triple knotted his shoes so that they would not become undone while he was in school.

Sadly for each person who supported Jim, there were detractors who teased him. He experienced several nicknames, such as 1.5.

For me, the most beautiful part of the book was Jim revealing meeting thousands of youngsters who had physical abnormalities. In every ballpark Jim played in, parents would ask the attendants to introduce their children to Jim. He would spend time with them, helping them understand that their disabilities would not block them from attaining wonderful accomplishments. Jim spent as much time with the youngster as with their parents. He wanted to convince the parents that their child could persevere.

Like most of us, Jim had to deal with life outside of baseball. Fortunately, he enjoys a wonderful marriage and has two daughters. Jim tours the country as a motivational speaker.

Originally published in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune