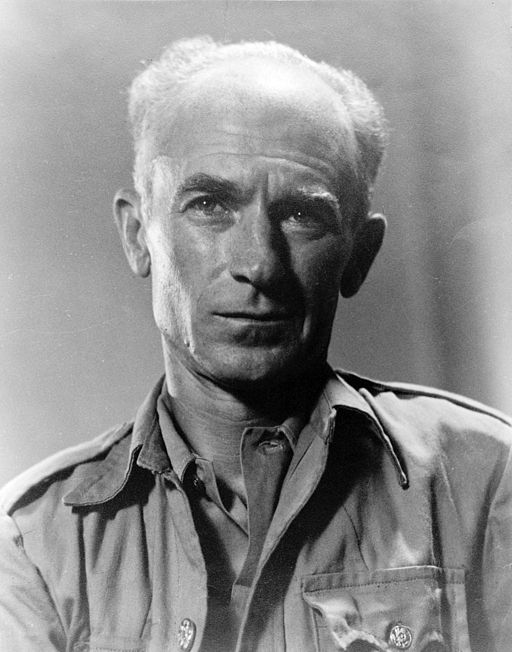

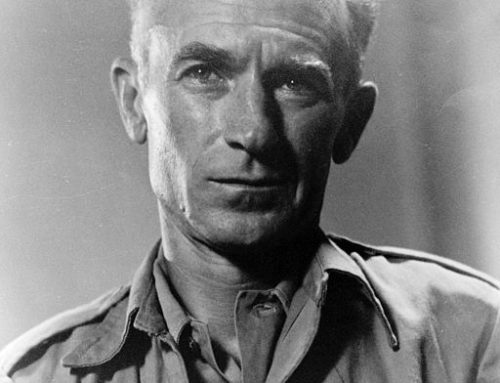

Ernie Pyle was beloved by readers and service members alike for his coverage of the war through the eyes of infantrymen on the front lines

In this week’s New York Times Magazine, the article was about my namesake, Ernie Pyle. My mother who herself was a pioneering journalist changed my name from Ernie Daniel to Ernie Pyle after the latter’s death during World War II in the Pacific Theatre.

Ernie Pyle was the first correspondent to describe accurately the war’s pain, costs, and losses. Specifically, Ernie Pyle accurately described the death of hundreds of soldiers taking the Omaha beach. Pyle reported the war through the eyes of the regular infantrymen on the front lines

In June 1944, Ernie Pyle, a 43-year-old journalist from rural Indiana, was as ubiquitous in the everyday lives of millions of Americans as Walter Cronkite would be during the Vietnam War. What Pyle witnessed on the Normandy coast triggered a sort of journalistic conversion for him: Soon his readers — a broad section of the American public — were digesting columns that brought them more of the war’s pain, costs and losses. Before D-Day, Pyle’s dispatches from the front were full of gritty details of the troops’ daily struggles but served up with healthy doses of optimism and a reliable habit of looking away from the more horrifying aspects of war. Pyle was not a propagandist, but his columns seemed to offer the reader an unspoken agreement that they would not have to look too closely at the deaths, blood and corpses that are the reality of battle. Later, Pyle was more stark and honest.

For days after the landing, no one back home in the States had any real sense of what was happening, how the invasion was progressing or how many Americans were being killed.

Nearly impossible to imagine today, there were no photographs flashed instantly to the news media. No more than 30 reporters were allowed to cover the initial assault. The few who landed with the troops were hampered by the danger and chaos of battle, and then by censorship and long delays in wire transmission. The first newspaper articles were all based on military news releases written by officers sitting in London. It wasn’t until Pyle’s first dispatch was published that many Americans started to get a sense of the vast scale and devastating costs of the D-Day invasion, chronicled for them by a reporter who had already won their trust and affection.

Pyle’s second report from the Normandy beaches, published 10 days after D-Day, was markedly different from anything he had ever previously filed. “It was a lovely day for strolling along the seashore,” he wrote, reeling the reader in with a cheerful opening. “Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them sleeping forever. Men were floating in the water, but they didn’t know they were in the water, for they were dead.” Pyle cataloged the vast wreckage of military matériel, the “scores of tanks and trucks and boats” resting at the bottom of the Channel, jeeps “burned to a dull gray” and halftracks blasted “into a shambles by a single shell hit.” Some reassurances followed to soften the unvarnished fact — the losses were an acceptable price for the victory, Pyle said — but he hadn’t shied away from showing his readers the corpses and “the awful waste and destruction of war.” Pyle was working up to something he hadn’t done before.

Pyle showed his readers the true cost of the fighting.

Pyle’s readers were confronted with outright horror: “As I plowed out over the wet sand of the beach,” Pyle wrote, “I walked around what seemed to be a couple of pieces of driftwood sticking out of the sand. But they weren’t driftwood. They were a soldier’s two feet. He was completely covered by the shifting sands except for his feet. The toes of his G.I. shoes pointed toward the land he had come so far to see, and which he saw so briefly.”

Pyle honed a sincere and colloquial style of writing that made readers feel as if they were listening to a good friend share an insight or something he noticed that day. When the United States entered World War II, Pyle took that same technique — familiar, open, attuned to the daily struggles of ordinary people — and applied it to covering battles and bombings.

Soon millions of readers were following Pyle’s daily column in about 400 daily and 300 weekly newspapers across the United States. In May 1944, Pyle was notified that he had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his dispatches.

I am leaving, Pyle wrote in his last column from Europe

The New York Times reported that enlisted men, officers, and a huge civilian public embraced Pyle because he spoke for the common infantryman. Pyle understood that there was no way the war could be a story with a happy ending given the millions of people killed and the damage to the survivors.