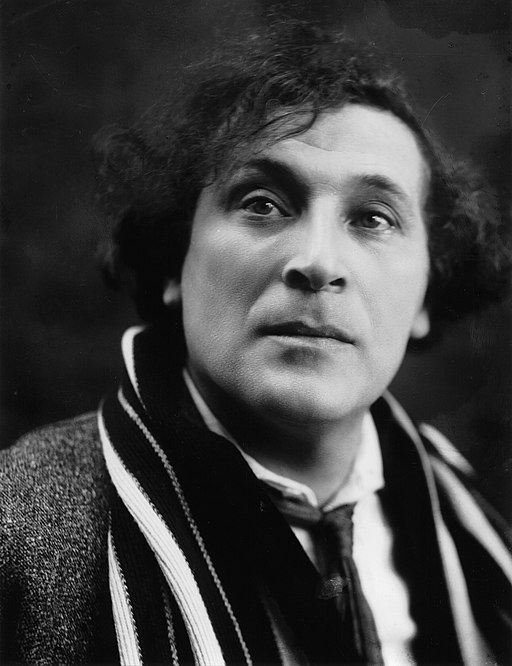

Eloise and I recently enjoyed the Chagall exhibit in San Francisco. He composed images based on emotional and poetic associations, rather than rules of pictorial logic. From the perspective of a critic, Chagall ranks as one of the foremost modern painters. From the viewpoint of a layman, his fanciful paintings with their rich hues are enchanting. . Chagall did not live long enough to paint the upcoming gubernatorial election in California. He would have thoroughly enjoyed the circus atmosphere of the upcoming election. The beheaded candidates would have been portrayed upside down. The voters might be looking aghast at the California spectacle from their rooftops or floating swimming pools.

His unique style set him apart from other artists of his time, and his imprint on modern art is indisputable. While he borrowed from Expressionism, Cubism, and even Abstraction, ultimately he created his own popular unique style. His repertory of images, including massive bouquets, melancholy clowns, flying lovers, fiddlers on roofs helped to make him one of the most popular innovators of the twentieth century. He presented dreamlike subject matter in rich colors.

During his long lifetime, he confronted oppressive government regulations dictated by tsarist, communist, and fascist regimes. Nevertheless, except for a period of five years following his first wife’s death in 1944, his works reflected fanciful optimism. In many ways he represented the roller coaster existence of the twentieth century. That is, he was born in a small village in the western Russian Empire portrayed eloquently in the musical Fiddler on the Roof. In order to become an artist he needed to overcome the obstacles of orthodox Jewish beliefs that being an artist was forbidden by the Biblical edict against graven images. Also Tsarists laws prohibited all but a handful of Jews from living in St. Petersburg, the Russian capital where the currents of modern European culture could actually be experienced. Ultimately, a combination of parental support, good luck, incredible natural talent, and persistence led to a breakout from these rigid constraints. In 1910, Chagall went to Paris where he met the Expressionist Chaim Soutine, the abstract colorist Robert Delaunay, and the Cubists Albert Gleizes, Fernard Leger and André Lhote. In such company nearly every sort of pictorial audacity was encouraged, and Chagall responded to the stimulus by rapidly developing his own unique poetic and surrealistic tendencies. Critics consider this period (1910-1914) might be his best phase. Representative works are Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers (1912), I and the Village (1911), and Paris Through the Window (1913). His colors showed resonance. The often-whimsical figures, frequently upside down, produced and suggest inner reverie and yet also reflect nostalgic memories of his childhood. He returned to these themes for the next sixty years. Chagall borrowed from cubism, but refused to be limited by what he saw as its narrow interpretation of the world. However, he used cubist methods to break up parts of he subject or scene giving his paintings their dreamlike quality: animals and people float in the air, realistic proportions do not limit depictions of objects.

At the beginning of World War I, Chagall returned to Russia where he remained for the next eight years. In 1915 he married the love of his life, Bella Rosenfeld. She appeared in many of his subsequent paintings. Initially Chagall was enthusiastic about the Russian Revolution, but after increasingly bitter aesthetic and political quarrels, he felt his work could become compromised if his work conformed to the accepted Party doctrine. In 1922, Chagall left Russia for good, leaving behind many of his works, including murals produced for the Jewish theatre. He worried that the subsequent brutal repressive Stalinist state destroyed these works. In an emotional return visit to Russia in 1972 he was pleasantly surprised to learn that his supporters had risked their careers and possibly their lives to preserve his works.

When Chagall returned to the West in 1923 he learned the techniques of engraving and printmaking. His etchings included themes to accompany the works of the Russian author Nikolai Gogol’s novel, Dead Souls, and the Bible. In 1931 Chagall traveled to Palestine to research the original locations of biblical events. His experience in the Holy Land deepened his feelings of solidarity with fellow Jews throughout the world. With Hitler’s rise to power, Chagall feared both the growing threat of world conflict and the renewed wave of anti-Semitism that gripped much of Europe. His powerful White Crucifixion (1938) he portrayed the crucified Christ at the center of the composition in a wrapped Jewish prayer shawl. He combined Jewish and Christian symbols. Lastly, he portrayed Nazi mobs terrorizing German Jews.

During most of World War II Chagall lived in the United States. 1n 1948, he settled permanently in the south of France near Nice, where his neighbors included Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. During the final phase of his career Chagall remained prolific. He painted a series of large paintings based on scenes from Jewish Scriptures, and now resides in the Marc Chagall National Museum outside of Nice. He compiled an impressive list of important commissions for public works including stained-glass windows at the Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, ceiling frescos for the Paris Opera, murals for New York City’s Metropolitan Opera House, stained-glass windows at the United Nations headquarters in New York City, and tapestries for Israel’s Knesset building in Jerusalem.