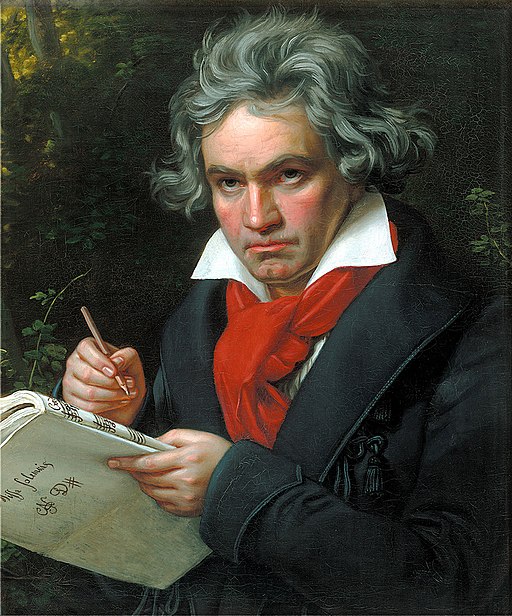

Ludwig van Beethoven remarkable compositions won him favor among the enlightened aristocracy congregated at Vienna, and he enjoyed their support throughout his life. They were tolerant, too, of his notoriously boorish manners, careless appearance, and towering rages. He composed many of his greatest works after the onset of deafness, starting in 1800. After 1817, he was completely deaf. In a letter written to his two brothers in 1802, Beethoven expressed his unhappiness over his affliction and suggested that death was near. Instead, he became even more determined and creative.

In 1792, Haydn invited him to become his student, and he remained in Austria for the rest of his life. However, Beethoven’s unorthodox musical ideas offended the old master, and the lessons were terminated. Beethoven studied under other eminent teachers, but developed such an independent style that he could not profit greatly from instruction.

Scholars generally divide Beethoven’s career into three distinct periods. The first period includes the First (1800) and Second (1802) Symphonies, piano sonatas, and string quartets. Although these compositions of the first period have Beethoven’s breadth and vitality, they are dominated by the tradition of Haydn and Mozart.

Beginning about 1802, Beethoven’s work took on new dimensions. The premier in 1805 of the massive Third Symphony, known as the Eroica (composed 1803-4), was a landmark in cultural history. It signaled a definite break with the past and the birth of a new era. The length, structure, harmonies, and orchestration of the Eroica all broke the formal conventions of classical music; unprecedented too was its intentional to celebrate human freedom and nobility. The Symphony was originally dedicated to Napoleon, who at first symbolized the spirit of the French Revolution and the liberation of mankind. However, after Napoleon proclaimed himself emperor, the disillusioned composer renamed his work the “Heroic Symphony to celebrate the memory of a great man.”

During this middle period, his most productive, Beethoven produced his sole opera, Fidelio, the Piano Concertos No 4 (1806) and No. 5 (Emperor Concerto), and a number of piano sonatas.

Beethoven’s final period dates from about 1816 and is characterized by works of greater depth and complexity. His string quartets are considered to be by music lovers to be his supreme creations.

Beethoven’s influence on subsequent composers has been immeasurable. He brought to music a new depth and intensity of emotion that was emulated by later romantic-composers.

On one occasion, when Beethoven was waling with Goethe, Goethe expressed his annoyance at the incessant greetings from passerby. Beethoven replied, “Do not let that trouble Your Excellency; perhaps the greetings were intended for me.”

When Beethoven composed, he considered himself at one with the Creator, and took endless pains to perfect his compositions. When a violinist complained that a passage was awkwardly written, Beethoven replied, “When I composed that I was conscious of being inspired by God Almighty. Do you think I consider your puny little fiddle when He speaks to me?”

When conducting his Ninth Symphony, Beethoven was completely deaf. He failed to hear the thunderous applause. One of the singers pulled at his sleeve and pointed to the audience. Beethoven turned and bowed.