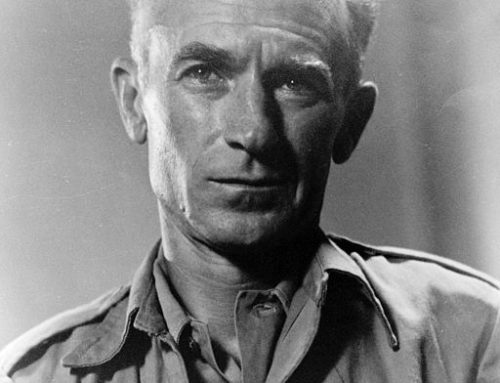

The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson

By Robert A. Caro

President Bill Clinton wrote the following in his review of Caro’s book, the Passage of Power. “After all the years of striving for power, once he had it, he said to the American people, “I’ll let you in on a secret — I mean to use it.” He used it to pass the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, the open housing law, the antipoverty legislation, Medicare and Medicaid, Head Start and much more.”

Robert Caro has spent much of his life writing about Lyndon Baines Johnson. Caro is sharply critical of Johnson, but he often stands in reluctant awe. Caro gives full credit to Johnson’s political skill after the assassination of John Kennedy catapulted him into the presidency.

Nevertheless, Caro has another message. Caro charged Johnson with the erosion of public trust in the American presidency. This is usually attributed to the disgraced administration of Richard Nixon, but actually began in the presidency of Lyndon Johnson. The term “credibility gap” has undermined faith in our political system since Johnson’s rule. The widespread popularity of the Tea Party Movement reflects legitimate anger at our political class because government has failed to raise our economic standards, ensnared us in misguided military ventures, and left us monumentally in debt that will enslave our children.

Caro has spent his lifetime seeking to analyze and understand Johnson. A major mission of Caro is to understand how a destitute, poorly educated man could grab onto the levers of power in a democracy. One of the ironies of Caro’s efforts is that Johnson assiduously acted with stealth to hide his intentions, his core belief system, and his unscrupulous accumulation of wealth. After nearly a half century in four volumes Caro has uncovered every element of Johnson’s life. The reader recognizes that Johnson’s story can best be understood through Caro’s writings.

Johnson frequently said “Power is where power goes.” However, during his three years as vice president Johnson found that this was erroneous. He might have agreed with his fellow Texan John Nance Garner, F.D.R.’s vice president, who famously described the office as “not worth a bucket of warm spit.”

Johnson did not have the same power as Vice President that he exercised in the Senate. Instead he was humiliated. The author spends much effort to articulate the depth and reasons for the hatred between Robert Kennedy and Johnson. While John Kennedy was president, Robert Kennedy emasculated Johnson. The Kennedy team heaped on Johnson the scornful title “Captain Cornpone.” The tables quickly turned after one shot on that fateful day in Dallas– Kennedy’s assassination.

In Caro’s fourth book of this series on Johnson, Caro focuses on how Johnson made startling legislative accomplishment. Indeed, Johnson was a master in the use of power. “To watch Lyndon Johnson during the transition is to see political genius in action,” wrote the author, who says no assessment of Johnson could ignore his “sureness of touch.”

As Caro shows in this and his preceding volumes, power ultimately reveals character. For L.B.J., becoming president freed him to embrace parts of his past that, for political or other reasons, had remained under wraps. Suddenly there was no longer a reason to dissociate himself from the poverty and failure of his childhood. Power released the source of Johnson’s humanity.

By contrast, the charismatic John Kennedy was inept. Under Kennedy we had a broken government. Nothing got done.

-

Kennedy could not pass a budget.

-

He could not implement liberal economic reforms.

-

He could not implement civil rights.

Johnson elevated the presidency to a focal point of presidential power comparable to the New Deal under Franklin Roosevelt.

.

A reviewer wrote:

“The Passage of Power,” encompasses the period of LBJ’s deepest humiliation and his greatest accomplishment. It is a searing account of ambition derailed by personal demons in Johnson’s unsuccessful bid for the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination. It is a painful depiction of “greatness comically humbled” when Johnson gave up his unbridled authority as Senate majority leader to become John F. Kennedy’s disdained vice president. Most of all, it is a triumphant drama of “political genius in action” as Johnson smoothly took up the reins of office in the wake of Kennedy’s assassination, made his predecessor’s liberal agenda his own, and bent Congress to his will as Kennedy had never been able to do. Caro combines the skills of a historian, an investigative reporter and a novelist in this searching study of the transformative effect of power — its possession, its loss, its restoration — on the character and destiny of a man who from his teens had one overriding goal: to be president of the United States.”

During the days immediately preceding Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson was at his lowest ebb. A public scandal was brewing involving his protégé Bobby Baker. The author reveals that Johnson used extortion to trade legislative favors for paid advertising on the Johnson radio and television stations. Such revelations would have dropped Johnson from the Democratic 1964 ticket. When Johnson became president he ruthlessly and efficiently “silenced the investigation into his malfeasance.”

Caro also described the heartless escalation of the Vietnam War. For purely political reasons, Johnson was committed to preventing the nationalistic hero Ho Chi Minh from gaining power in South Vietnam. Johnson believed that to “lose South Vietnam to communism” would hurt his re-election chances in 1964. In order for Johnson to keep the “reins of power” he was prepared that hundreds of thousands of Americans suffer and millions of Vietnamese to die. Johnson lied to Congress and the American people about the costs of the Vietnam War as well as the ineptness of the junta that ruled South Vietnam.

Johnson even broke with Martin Luther King over the war. King understood that Vietnam emasculated Johnson’s “war on poverty” and civil right advances. We could not have both “guns and butter.”

Caro’s harsh treatment of Johnson’s despicable actions prompts me to wonder why he devoted his life to this contemptible character. Caro argues that Johnson used his power to wield enormous impact on our urban and national development. Caro feels that someone needs to explain how power is used and abused is vital to preserving democracy. Now that I understand how Johnson amassed $ millions from relatively small earnings as a public servant, I wonder whether the American people have the “will and knowledge” to prevent our current political class from similar abuses. We learn that under Johnson, the “so-called” blind trust of politicians is a cruel ruse. We learn how Johnson forced the Houston Chronicle to write favorable articles about him in return for approving a bank merger that benefitted the owners of the newspaper. We learn how he “blackmailed a Forth Worth” newspaper in return for elevating a major air force base in the area. In brief, Johnson had no moral scruples.

.