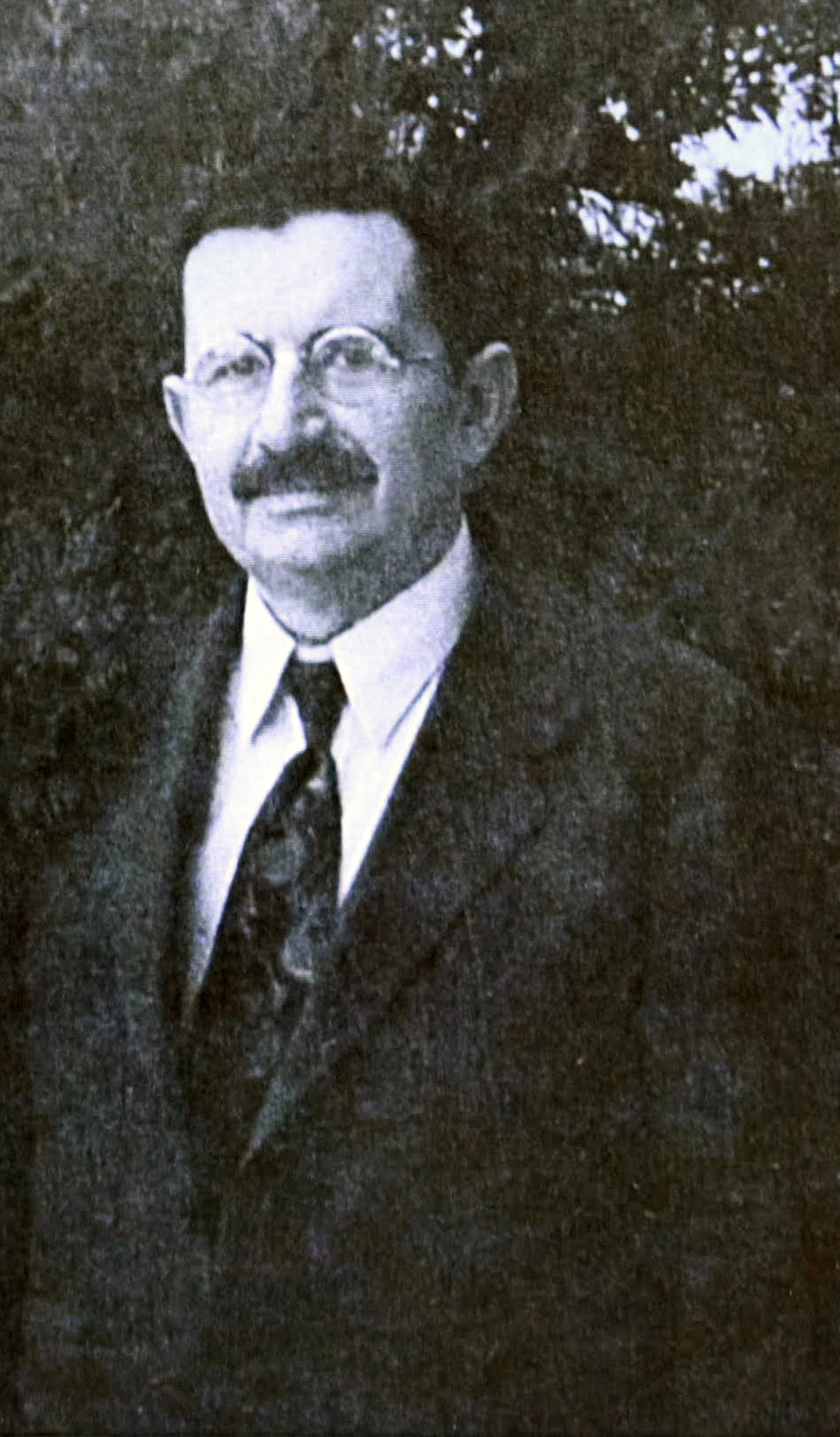

Jacob Werlin. Photo courtesy of Ernest Werlin

My grandfather, Jacob Werlin, represented a significant group of self-taught Jewish intellectuals bred in the poverty and virulent anti-Semitism of Eastern Europe. These men spent almost all of their non-working life reading and writing about Jewish and Zionist subjects. Jacob Werlin and subsequently my mother and father wrote countless articles for the Jewish Herald over their lifetimes. In fact, the Jewish Herald, altered their publication to reflect the death of my mother in 1985. That is, the paper had been even printed when they learned belatedly of her death. Nevertheless, they rewrote the paper to honor her.

My grandfather died before I was two. Thus, I do not remember him. However, from all accounts he was a gentleman and scholar. In fact, he owned the first Hebrew typewriter in Texas—a typewriter that was bequeathed upon his death to my other grandfather, Henry Horowitz. The typewriter currently resides with my cousin, Bonnie Kotlar, who is a very devout Jew.

Jacob Werlin was part of the West of Hester Street Movement. That is, in recognition of the growing anti-Semitism toward Eastern European Jews who populated the slums of the Northeast, German Jews financed the relocation of thousands of Jews to the West—their primary port of call was Galveston, Texas, which was the most populous city in Texas in the early part of the twentieth century. The movement of Jews to Texas was stopped by the KKK during World War I. That is, Galveston became more difficult to gain entry than Ellis Island.

The caption reads: “Extreme Left: Neighbor’s Auto Loaned for Photo. The Jacob B. Werlin and

Family Go Farming in Pearland, Texas-1910-1912.” Texas Jewish Historical Society Records, di_09436, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Jacob Werlin moved initially to Pearland, Texas around 1907. While I do not know in detail his early vocations, I am aware of two failed enterprises. First of all, along with his brother-in-law he founded a garment shop in Houston. Also, believing that for Jews to be accepted in America, he felt that it was imperative for Jews to own land. Thus, he had a small farm in Pearland, Texas. In those days, there were daily trains from Pearland to Houston.

It is my understanding that after work, Grandfather Werlin devoted much of his time writing on either religious or Zionist tracts. Ironically, because he was such a poor businessman, his four sons—Joseph, Eugene, Reuben, and Sam—became lukewarm both toward organized religion and Zionism.

English was either a third or fourth language for Jacob Werlin. Although he wrote beautifully, Tom Werlin’s mother told me that he mispronounced many words. Irrespective of this handicap with English, he was sought after as a speaker both for Jewish and Zionist causes. In those days, many Jews spent evenings listening to learned lectures. This is understandable given that radio did not become popular until the late 1920’s.

Jacob Werlin attended the first Zionist conference in Waco, Texas in 1917. Indeed the founding of a Jewish State was the major mission of his life.

Like many Jews, education was highly stressed. Thus, in an era when few people went to college, my father and his brothers all got degrees from Rice Institute. My father, who never graduated from high school, ultimately received a doctorate from the University of Chicago, 1933.