By Jeff Shesol

“If the Court-Packing plan passed, the court will become as ductile as a gob of chewing gum, changing shape from day to day and even from hour to hour as this or that wizard edges his way to the President’s ear.”

-H.L Mencken

Introduction:

Jeff Shesol, a Rhodes Scholar and former speech writer for Bill Clinton, wrote a fascinating account-“Supreme Power”- of the struggle for power between our three branches of government—The Executive, the Supreme Court, and the Senate that took place almost 75 years ago. His account of Franklin Roosevelt’s failed attempt to pack the Supreme Court with his judicial preferences had all the intrigue of a Machiavellian Court.

Interestingly enough, Roosevelt might have won his battle against the Supreme Court. That is, subsequent to his failed Court Packing plan a majority of the Supreme Court decided to support many of his New Deal programs. Over time, he replaced his Conservative enemies on the court, with Liberals.

However, FDR lost badly his desire to remain in control of the legislative branch. That is, after 1937, Roosevelt never again could pass major Domestic social reform legislation. Ironically, FDR aimed his gun in the “wrong direction.” It became the most controversial proposal of his presidency — so much so that it nearly paralyzed his administration for over a year and destroyed much of the fragile unity of the Democratic coalition. Losing control over the Legislature was for more devastating to his power base than defeating the Supreme Court.

For those of you who share my fascination about how groups attain and wield power in a Democracy, I recommend “Supreme Power”. We need to remember the challenge that faces any person or group that wants to remain in power. They must recognize that similar to a wind surfer, one wrong move can capsize a career. Thus, the need to keep to keep one’s balance while moving forward remains an on-going challenge.

Court Packing Scheme

Roosevelt’s scheme was to achieve a majority by having Congress grant him authority to appoint an additional justice for every serving member older than 70 – six justices. He acted in deep secrecy, ignoring Congress. Warner W. Gardner, a 27-year-old lawyer in the solicitor general’s office, did the bulk of the drafting. To make the scheme ‘less smelly’, Roosevelt and aides revised Gardner’s work and dubbed it a Judicial Reform Act” on the false grounds that the judiciary was overwhelmed with work. A furious Gardner kept his mouth shut for the moment, but later he would call the ploy an “effort to market deceit” and an exercise in Madison Avenue sleaze.

Roosevelt Motivation

Roosevelt had political motivation to go after the court, that seemed bent on cutting the heart from his New Deal programs. The court demolished program after program: The National Recovery Administration, with its panoply of minimum wages, maximum hours and workers rights; a farm relief program; state minimum wages; and many other acts. Shesol wrote that “No Supreme Court in history had ever struck down so many laws so quickly. Between 1933 and 1936, “the Court overturned acts of Congress at ten times the traditional rate.”

Congress Opposition

Congressmen quickly saw through the sham. When the bill was read in the Senate, Vice President John Nance Garner ostentatiously held his nose and gave a thumbs-down signal. Outnumbered Republicans made a wise political decision; they were initially muted in their opposition. Over time they sought out Conservative Democratic allies. Even though congressional Democrats voted overwhelmingly for New Deal measures, many legislators remained deeply skeptical. Sen. Henry Ashurst, Arizona Democrat, conveyed his worries in his diary “behind the facade of fear and need, Congress had made experiments on a grand scale and temporarily transmuted our way of life from individualism into regimented state socialism…. For aught we know, the Congress may have done what Russia did by her bloody revolution.”

The Historical Events: FDR “The Prince”

In 1932, Franklin Roosevelt started an unprecedented 4 terms as President. His mission was to end the Great Depression. Unsurprisingly, Roosevelt faced obstacles, including opponents within the Republican Party, some members of his own party and tradition-bound members of the electorate (despite his overwhelming margin in the popular vote). Others blocking the way were veteran bureaucrats within the executive branch who found it difficult to adapt to a more activist government and, most prominently, the United States Supreme Court. The “nine old men” with lifetime appointments included at least five who regularly overturned Roosevelt initiatives to fight the Depression, ruling those initiatives to be unconstitutional.

By early 1937, FDR had attained almost omnipotent powers. He had led a successful democratic ticket to spectacular victories over the historically dominant Republican Party. Roosevelt carried 46 states in 1936. Democrats held overwhelming number of seats in both the House and the Senate. Until 1937, Roosevelt truly had mastery over the levers of government. For example, in the hectic first few days of the New Deal, legislation was passed even before Congress had printed versions of the proposed bills!

The Supreme Court

The only opposition to “one-man rule” was the Supreme Court. The justices of the Supreme Court were as sharply divided in the 1930s as they often seem to have become in the 21st century. Five of them (George Sutherland, James McReynolds, Willis Van Devanter, Pierce Butler and Owen Roberts) were largely opposed to the New Deal measures they were asked to consider. Three other judges (Louis Brandeis, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Benjamin Cardozo) supported the New Deal. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes was in the middle—sometimes opposing and sometimes supporting.

In 1937, when the court-packing fight began, most of the justices had been on the bench for well over a decade, and none had been appointed during Roosevelt’s first four years. Given its long tenure and conservative disposition, the President believed that the court had become ‘out of touch’ with the realities of the time.

Interestingly enough FDR could have let ‘father time’ work for him. All four conservative judges—Pierce Butler, Willis Van Devanter, James McReynolds, and George Sutherland– resigned by 1942. Almost all of they resigned for health and age reasons. However, as the Court swung increasingly to the Left, some of them became frustrated at being ignored.

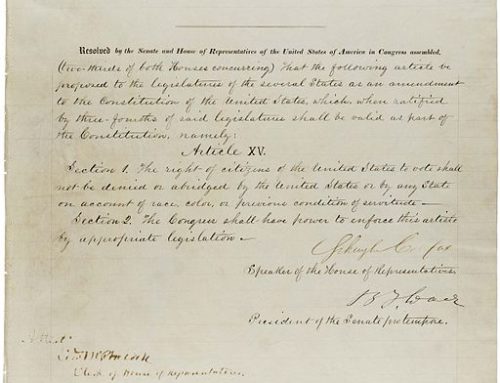

The Constitution

Interestingly enough, the ‘framers’ of the U.S. Constitution in 1787 designed the judiciary to be the weakest branch of government. Alexander Hamilton the influential writer of the Federalist Papers that were instrumental in obtaining passage of the Constitution noted that the Supreme Court “has no influence over either the sword or the purse.” Nevertheless, under its most powerful Chief Justice, John Marshall, the Supreme Court made decisions that greatly expanded its powers. For example, the Supreme Court asserted its right to rule on the constitutionality of legislative acts (Marbury v. Madison) and thereby established the precedent of “judicial review.” The Supreme Court’s decisions following the Civil War to provide broad relief to corporations seeking “substantive due process” protection under the 14th Amendment greatly enhanced the power of the court. Alex de Tocqueville in the 1830s noted “The peace, the prosperity, and the very existence of the Union are placed in the hand of he judges. Without their active cooperation, the Constitution would be a dead letter.”

FDR’s Political Moves

FDR felt that the landslide of the Democratic Party in the 1936 national elections was a vindication of his policies. Therefore, he fretted that putting New Deal policies under the scrutiny of a few justices undermined “popular will.”

FDR plotted his move against the Court with great secrecy. Instead of consulting key leaders of the House or Senate, he worked with longtime loyalists such as Judge Sam Rosenman, Tommy “the Cork” Corcoran, and Attorney General Homer Cummings.

FDR’s congressional opponents had to move skillfully to defeat the president. They ultimately won the battle of popular opinion by courting key newspapers. They got reclusive Chief Justice Charles Hughes to “come out swinging.”

Opposing the popular president who wielded enormous patronage clout was a calculated risk. To assure passage Roosevelt promised Senate Majority Leader Joe Robinson a coveted seat on the Supreme Court. Roosevelt’s defeat on the Court Packing Bill in 1937 was his first defeat on a major legislative initiative since assuming the presidency in 1933. Roosevelt tried unsuccessfully to engineer the ‘political defeat’ of his conservative democratic foes in 1938 and 1940.

However, opposition eventually coalesced. Conservative Democrats who represented close to 50% of the party forged an alliance with the few remaining Republicans. Conservative Vice President John Nance Gardner broke with FDR over the Court plan. He even “held his nose” as a sign of displeasure. FDR’s obstinate failure to compromise in time showed terrible judgment. Lawyers overwhelmingly opposed the President feeling the Supreme Court was indispensable to maintaining “Checks and Balances.” Even the hard-pressed public sensed that FDR had gone too far. Ultimately, FDR lost by a vote of 70-20. America remained committed to the notion that even under the threat of a economic collapse “we remained a nation of laws not men!”

Conclusion

Supreme Power is by far the most detailed — and most riveting — account of FDR’s Court Packing Plan. Both sides of the controversy were the products of deep conviction. The court was on a mission to combat what the justices viewed as a great danger to the basic principles of American democracy. The White House was on its own mission to save not just the New Deal, but also its restoration of the nation.

The dangers of the court-packing plan quickly became clear. The opposition to the court-packing plan was much greater than Roosevelt and his advisers had imagined. It was not surprising that the court-packing controversy would arouse the rage of the right, which already detested Roosevelt and the New Deal and believed the White House was building a dictatorship. More startling to the president was the outrage from within his own party — even among many staunch progressives. Roosevelt over time only received lukewarm loyalty from his few remained supporters. Many opponents of the proposal shared Roosevelt’s dismay at the court’s conservatism, but tampering with the institution seemed even to many liberals to represent excessive presidential power and a threat to the Constitution.

In July 1937, the court proposal died in the Senate, by now undefended even by the White House and unlamented by most of the public. It was widely described as the most devastating defeat Roosevelt had ever experienced. It became the most controversial proposal of his presidency — so much so that it nearly paralyzed his administration for over a year and destroyed much of the fragile unity of the Democratic coalition.

“Supreme Power” is an impressive and engaging book — an excellent work of narrative history. It is deeply researched and beautifully written. Even readers who already know the outcome will find it hard not to feel the suspense that surrounded the battle, so successfully does Shesol recreate the atmosphere of this great controversy. There are many ways to explain what become known as the “Constitutional revolution of 1937,” but Shesol’s book is the most thorough account of this dramatic and still contested event. Fortunately, our founding fathers understood that for a democracy to remain vibrant we need a balance of powers.

Originally published in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune