Pulitzer Prize winning author, Nick Kotz, wrote a compelling history of the fight for civil rights. The book primarily focuses on the extraordinary effectiveness of President Lyndon Johnson to pass the Civil Rights Acts of 1964, 1965, and 1968. Kotz marvelously highlighted the brilliant maneuvers Johnson deployed to overcome opposition. Despite one’s admiration for his energy, courage, and mastery of legislative techniques, Johnson remains a flawed figure. He relentlessly demanded center stage, and brutally upstaged liberal allies such as Hubert Humphrey, and Mike Mansfield. He ordered FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to operate outside the law to leverage executive authority over anybody challenging his authority.

Time has been cruel to Johnson. He is more remembered for his failures in Vietnam than for civil rights legislation and the War on Poverty. Despite incredible accomplishments not only in civil rights but advancing liberal legislation, historians give Johnson mediocre ratings. Ironically, Martin Luther King’s stature has risen to mythical proportions. We now celebrate his legacy with a national holiday. His celebrated “I have a Dream Speech” is known by every school child. Nevertheless, King’s role in advancing Civil Rights legislation pales in comparison to Johnson. In contrast to King, Johnson who fought as ferociously for favorable publicity as he did for legislative accomplishments has receded from public memory. The United States is a very different society today than it was in 1963—thanks in large part to the Johnson presidency and the most liberal Congress since the Great Depression. The stark problems of poverty still facing much of our nation, and in particular many black Americans, leads some critics to dismiss the decade of the 1960s as one in which little meaningful change occurred. Others would argue that instead of government being an instrument of progress, it is “the problem.” Nevertheless, the country is still better off now that the cruel legal structures of segregation have ended.

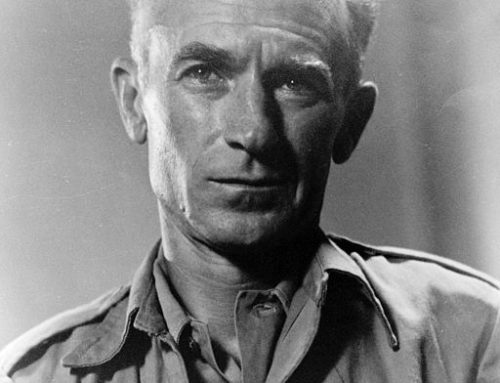

Several months ago, Charlie Rose interviewed Robert Caro, who has written extensively on Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson. Rose asked Caro why he devoted his life to such exhaustive writings on these two men. Caro responded that he was obsessed by understanding how men in a democracy use power to implement their agenda. In chronicling their lives, Caro sought to illuminate the illusion that America is just a nation of laws. Men like Moses and Johnson believed that the end justified the means. They mastered intricate knowledge of the legislative process to push through their extensive agendas. In Johnson’s case, he ceaselessly studied people, learning their likes, dislikes, needs, weaknesses, and fears. He employed everything to advance his agenda. Unfortunately for Johnson, he had no life outside of politics. He died an embittered old man a few years after leaving the presidency. Specifically, he felt isolated and useless for he was blackballed from the councils of power by even his own party.

Two other men appear prominently in the book, Martin Luther King and J. Edgar Hoover. Today, King towers above other leading civil rights leaders of that era such as Roy Wilkins, the head of the NAACP, Whitney Young, the head of the Urban League, and Thurgood Marshall, the nation’s first black Supreme Court Justice.

Until King’s assassination, his legacy was debatable. King had several flaws that could have marred Civil Rights. King was a notorious womanizer and collaborated with communists. While King did a masterful job of orchestrating a massive Afro-American movement, he never focused on the intricacies of civil rights legislation. Kotz’s narrative highlighted that winning civil rights legislation required mastery of intricate details, a Johnson specialty.

J. Edgar Hoover, who headed the FBI from 1924-1972, was a terrifying figure. A white racist he sought to discredit civil right leaders by making communist charges against them. Hoover tried to emasculate any effective FBI action to monitor and curb the activities of the Ku Klux Klan. Hoover was obsessed with destroying King. He relentlessly used FBI files to destroy King’s reputation. Hoover even hoped to persuade King to commit suicide. That is, Hoover admonished King that he would publicize his extramarital affairs unless King killed himself.

One question that the book never fully explained was why Johnson was obsessed by passing civil rights legislation. Let me highlight Johnson’s dilemma. Johnson was obsessed by power. He understood fully that in fighting for civil rights he was using up his political capital. He was fighting entrenched forces of reaction. Southern control of key Congressional committees historically prevented legislative relief. Even in the North, many Democrats harbored strong segregationist’s viewpoints. George Wallace, Alabama’s notorious race baiting governor, carried over 30% of the primary vote in Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan in 1964. The South had historically employed the filibuster to stop civil rights legislation. At that time, 67 votes were needed for closure. The South traditionally counted on support from conservative Republicans who also felt that the filibuster prevented tyranny from populous liberal power blocs. In essence, the filibuster was considered the key weapon in keeping a “balance of power.”

One possible explanation for Johnson’s civil rights passion was Johnson’s emotional connection with the disadvantaged. Johnson genuinely wished to eliminate poverty with his Great Society Programs. He understood the contradiction of uplifting Hispanics and Afro Americans economically and denying them equal rights. Johnson felt that the failure of the New Deal to empower the poor left them wards of the establishment.

Forty years after Johnson’s legislative victories in the fields of civil rights and great society programs, millions of Americans still live in the iron-grip of poverty. The interwoven problems of broken families, teenage pregnancy, crime, drugs, inadequate schools, and lack of jobs have led to the loss of hope. Moreover, Americans no longer believe that we have such abundant resources that we can “blindly throw money at problems.” Moreover, many government programs have become mired in bureaucratic paper shuffling rather than instruments of progress.

In conclusion, I share the negative feelings toward Johnson. While in 1964 and 1965 I was proud that a fellow Texan was leading the nation in so many wonderful endeavors, by 1967 I had turned against the Vietnam War. I share Martin Luther King’s criticism of the Vietnam War; that is, our nation could not afford both guns and butter. In the end, our military power was impotent in the face of Vietnamese nationalism and our butter became rancid. The terrible inflation of the 1970’s was a direct result of our failure to pay economically for the Vietnam War. In essence, Johnson’s Great Society Programs lost their effectiveness as the nation coped with the staggering burdens of Stagflation.