There’s something to be said for leaving things as you found them, but not when it pertains to stock performance.

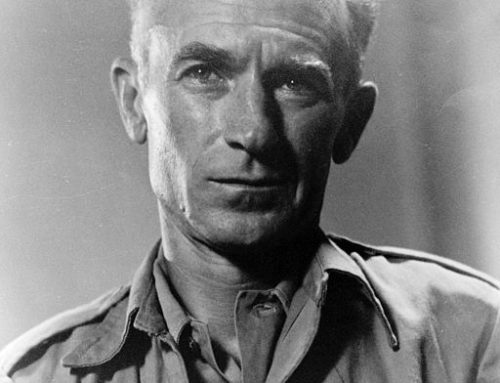

Soon after Larry Kellner became chief executive officer in late 2004, shares of Continental Airlines slid below $10 a share. Thursday, just before he announced his retirement, they closed at $9.96.

Continental is, of course, an airline, which means executive achievement never goes unpunished by the marketplace.

In between to sub-$10 bookends to Kellner’s tenure, Continental’s shares soared to more than $51 and Kellner moved Continental into a leadership position among the major carriers. He fought off what would have been a disastrous merger with United, expanded Continental’s lucrative international route system and maintained what passes for labor peace in the airline industry.

He kept Continental out of bankruptcy court while most of his rivals succumbed, and he weathered record oil prices last summer that hammered the industry’s finances.

But perhaps Kellner’s greatest achievement wasn’t what he did, but what he didn’t do. Stepping into the CEO’s job after the flamboyant Gordon Bethune, Kellner managed to bring his own subdued style to the job without sacrificing the stunning turnaround engineered under his predecessor.

“Kellner should be roundly applauded,” said Mike Boyd, president of the Boyd Group/ASRC, an industry consulting firm. “He wasn’t a clone, but Continental stayed the same.”

In any other industry, staying the same might seem like faint praise, but as I said, this is the airline business. Success is measured by making it to the next crisis. Yet Kellner always seemed unaffected. His affable demeanor was a stark contrast to the chain-smoking stress that seemed to pervade executives of the post-regulation years.

By the time he leaves office at year’s end, Kellner will have logged five years in the CEO’s job. He joined Continental in 1995, part of a team of smart finance guys brought in under Bethune and financier David Bonderman to break the industry’s persistent flirtation with insolvency.

They didn’t achieve that, but Continental is a far better airline now than it was then. Rising through the finance side of the business, Kellner helped instill a discipline that spurned the industry’s bad habits, such as grabbing market share at any cost or merging simply to get bigger.

“They know what they want to be,” Boyd said. “They’re not listening to the Wall Street lore.”

By keeping Continental out of bankruptcy, Kellner faced a new problem. The four carriers that last went through Chapter 11 now have lower costs, leaving Continental at a disadvantage. Under Kellner, though, the carrier stuck to services that, while expensive, make a difference to passengers. He kept in-flight meals, maintained a young fleet and offered amenities such as in-flight movies on domestic flights. Only grudgingly did he join the rest of the industry in tacking on fees for things like checking baggage.

“Overall, it’s high-quality product, and that doesn’t happen by accident,” Boyd said. “They’ve had good leadership.”

Now, Kellner may be getting out while he has the chance. The recession has gutted high-dollar business travel, last quarter’s swine flu scared away passengers and jet fuel prices rose 32 percent. Continental is expected to report its seventh straight quarterly loss next week, and the industry may be bracing for another of its perennial bankruptcy binges.

“Anybody who can escape from the airline business, that’s escape from employment Alcatraz,” Boyd said.

So Kellner heads for the door, and Continental’s stock sinks back to the level it was when he started. That says more about the industry than it does him. The share price may be the same, but he leaves Continental a better airline.