“We cannot, we must not, and we will not let our auto industry simply vanish. This industry is, like no other, an emblem of the American spirit; a once and future symbol of America’s success. It is what helped build the middle class and sustained it throughout the 20th century. … But we also cannot continue to excuse poor decisions. And we cannot make the survival of our auto industry dependent on an unending flow of tax dollars. These companies — and this industry — must ultimately stand on their own, not as wards of the state.”

— From March 30 remarks by President Barack Obama

The president provided a rationale for his decision to save Chrysler and General Motors — they represented an integral part of an industry that contributed 10 percent of our gross national product and provided middle-class employment to hundreds of thousands.

Over time, we will learn whether American automobile companies can survive. In America they compete against non-union foreign companies. Abroad, they face manufacturers in low labor-cost countries such as South Korea, India and China.

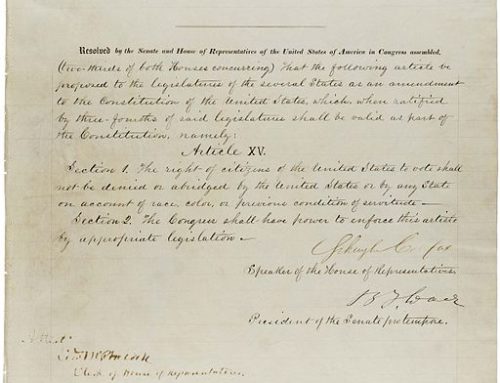

Aside from the daunting financial challenge of saving GM and Chrysler, Americans hold different views about the role the state should play in economic activities. One view, laissez faire, is that the state’s role be relegated to establishing a minimum number of rules to ensure that the market economy functions successfully. Another perspective envisions government intervening in a broad range of industries such as high-risk technology sectors, education and the health industry.

The Obama administration’s decision to save Chrysler and GM led to radically different outcomes from their destiny in a free market economy. Specifically, we interfered with a historic litmus test of capitalism — “creative destruction.” The term, coined by Joseph Schumpeter in his 1942 work “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy,” denoted a “process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” Historically we endorsed creative destruction of “horse buggy businesses” because we believed that our entrepreneurs could create superior enterprises.

For decades, America has relied on a combination of private and public enterprises. For example, we subsidized economic companies in areas such as defense, energy and transportation. A majority of Americans now favor a larger role for the federal government in promoting industrial policies that emphasize the cooperation between government, banks, private enterprise and employees.

The White House has made auto policies that historically were rendered in the corporate board room such as:

GM should divest of Saab and Opel.

GM was relying too much on high-margin trucks and SUVs.

Chrysler should merge with Italian automaker Fiat.

Critics argue that the above steps are inconsistent and economically irrational. They contend that the U.S. is a post-industrial economy that cannot cost-efficiently manufacture most products.

America is the world leader in finance, information and business services. Fortunately for America, services outweigh manufacturing in terms of their contribution to the world’s gross domestic product: 65 percent for servicing versus 17 percent for manufacturing. The United States provides 32 percent of world service output, far greater than any other country.

Former GM Chairman Charlie Wilson is given attribution for the phrase “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country.” The Obama administration adheres to these sentiments.

Nevertheless, we need to strike a balance between saving the livelihood of thousands of autoworkers and establishing a regimen that keeps our auto companies globally competitive. Otherwise we could be digging a bottomless pit.

Originally published in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune