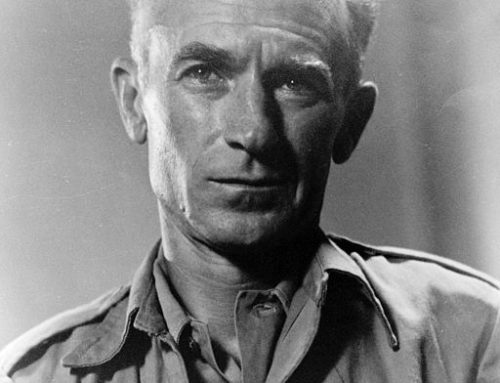

Several weeks ago, I was fortunate enough to attend an 80th birthday commemoration for Elie Wiesel at the 92nd Y. In hindsight, I wish over the years I had attended more of his lectures because his voice for the downtrodden serves as a constant moral compass. My absences reflected my own vacillation between “doing the right thing” and “wanting escapist entertainment.”

The momentous events of the twentieth century transformed the expected life pattern of Wiesel. This is, he was born into a devout but provincial family in an undistinguished village of Romania (his hometown’s nationality has vacillated like the wandering Jew.) He has emerged from the holocaust to become a spokesman for our time, communicating the need for our generation to speak out against inhumanity. Wiesel received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 in recognition of his devotion to articulating the plight of modern-day victims. His plea for “Never Again” has focused on worldwide inhumanity by authoritarian leaders in such disparate countries as South Africa, Sudan, Ethiopia, Soviet Union, Argentina and Yugoslavia. As the world’s most renowned writer of the Holocaust, Wiesel teeters between being a devout Jew and agnostic existentialist. Wiesel constantly asks the silent God, whom Elie revered without doubts until entering the death camps at age 16, to respond to his accusations of abandonment.

Wiesel might have broken his vow of silence on the holocaust over time. Fortunately, the French Nobel Prize winning writer Francois Mauriac convinced Wiesel of his need to be a “witness.” Mauriac, a devout Roman Catholic, had been haunted by his wife’s description of seeing Jewish children torn from their parents and being sent on train loads to “unknown destinations” during the German occupation of France.”

Mauriac said these words in the preface to Night. “But these lambs torn from their mothers that were an outrage far beyond anything we would have thought possible…. And yet I was still thousands of miles away, from imagining that these children were destined to feed the gas-chambers and crematoria.” Mauriac went on to say “Have we ever considered the consequence of less visible, less striking abomination, yet the worst of all, for those of us who have faith: the death of God in the soul of a child who suddenly faces absolute evil?”

Wiesel in his preface to his book, Night, writes that this book embodies his reason for being. He feels strongly that he must be a witness not only for the millions that died in the Nazi death camps, but for future victims of heinous crimes.

Elie Wiesel’s statement, “…to remain silent and indifferent is the greatest sin of all…”stands as a succinct summary of his views on life and serves as the driving force of his work. Wiesel is the author of 36 works dealing with Judaism, the Holocaust, and the moral responsibility of all people to fight hatred, racism and genocide. Wiesel has since dedicated his life to ensuring that none of us forget what happened to the Jews because his people represent the longing of all humanity to survive and perpetuate their traditions.

In his youth, Eliezer Wiesel led a life representative of many Jewish children. Growing up in a small village in Romania, his world revolved around family, religious study, community and God. Yet his family, community and his innocent faith were destroyed upon the deportation of his village in 1944. Arguably the most powerful and renowned passage in Holocaust literature, his first book, Night, records the inclusive experience of the Jews:

Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky.

Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever.

Never shall I forget that nocturnal silence which deprived me, for all eternity, of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself.

Highlights of Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech, Delivered in Oslo on December 10, 1986

Wiesel reminded his audience of the Jewish tradition to recite this prayer on special occasions “Blessed be Thou… for giving us life, for sustaining us, and enabling us to reach this day.”

Wiesel acknowledged that while he cannot speak for all the dead of the Holocaust, he reminded the audience of his endurance and survival in the Kingdom of Night. Wiesel recounted asking his father on the first night in the concentration camps “Can this be true? This is the twentieth century, not the Middle Ages.” Wiesel answered his own question with the statement that “he has tried to keep the memory alive, that I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.” Wiesel felt that the world did know about the holocaust and remained silent. And that is why I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human being endure suffering and humiliation.

In conclusion, we should note that for at least fifteen years following the end of World War II, silence stopped discussion of the holocaust. Only a few thousand copies of Night were published in its first few years following its publication in 1960. Irrespective of the immediate apathy to a book Wiesel continued to communicate about the holocaust because he felt that he needed to take responsibility. “The witness has forced himself to testify. For the youth of today, for the children who will be born tomorrow. He does not want his past to become their future.”